It’s meat.

The two commodities share a great deal: Like oil, meat is subsidized by the federal government. Like oil, meat is subject to accelerating demand as nations become wealthier, and this, in turn, sends prices higher. Finally — like oil — meat is something people are encouraged to consume less of, as the toll exacted by industrial production increases, and becomes increasingly visible.

Global demand for meat has multiplied in recent years, encouraged by growing affluence and nourished by the proliferation of huge, confined animal feeding operations. These assembly-line meat factories consume enormous amounts of energy, pollute water supplies, generate significant greenhouse gases and require ever-increasing amounts of corn, soy and other grains, a dependency that has led to the destruction of vast swaths of the world’s tropical rain forests.

Just this week, the president of Brazil announced emergency measures to halt the burning and cutting of the country’s rain forests for crop and grazing land. In the last five months alone, the government says, 1,250 square miles were lost.

The world’s total meat supply was 71 million tons in 1961. In 2007, it was estimated to be 284 million tons. Per capita consumption has more than doubled over that period. (In the developing world, it rose twice as fast, doubling in the last 20 years.) World meat consumption is expected to double again by 2050, which one expert, Henning Steinfeld of the United Nations, says is resulting in a “relentless growth in livestock production.”

Americans eat about the same amount of meat as we have for some time, about eight ounces a day, roughly twice the global average. At about 5 percent of the world’s population, we “process” (that is, grow and kill) nearly 10 billion animals a year, more than 15 percent of the world’s total.

Growing meat (it’s hard to use the word “raising” when applied to animals in factory farms) uses so many resources that it’s a challenge to enumerate them all. But consider: an estimated 30 percent of the earth’s ice-free land is directly or indirectly involved in livestock production, according to the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization, which also estimates that livestock production generates nearly a fifth of the world’s greenhouse gases — more than transportation.

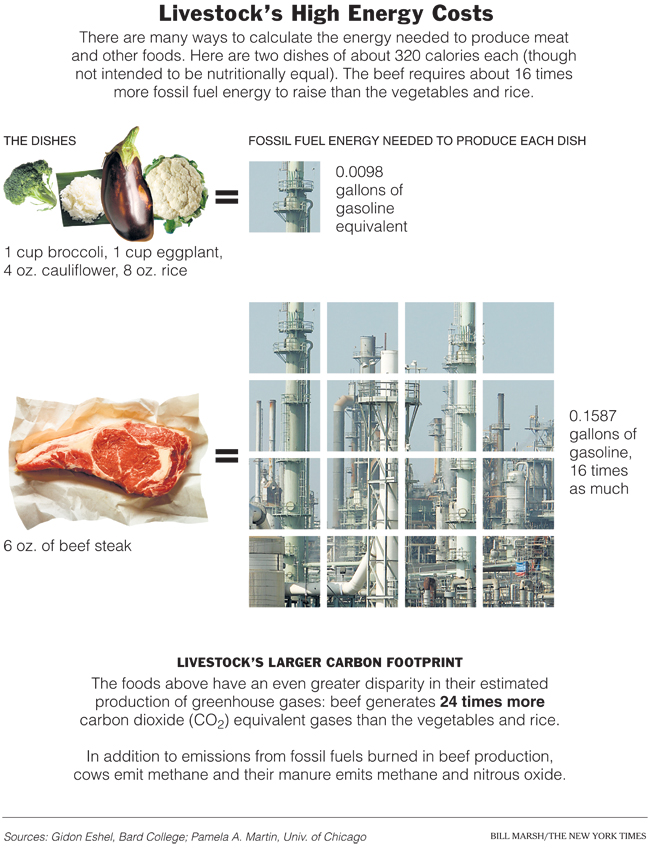

To put the energy-using demand of meat production into easy-to-understand terms, Gidon Eshel, a geophysicist at the Bard Center, and Pamela A. Martin, an assistant professor of geophysics at the University of Chicago, calculated that if Americans were to reduce meat consumption by just 20 percent it would be as if we all switched from a standard sedan — a Camry, say — to the ultra-efficient Prius. Similarly, a study last year by the National Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science in Japan estimated that 2.2 pounds of beef is responsible for the equivalent amount of carbon dioxide emitted by the average European car every 155 miles, and burns enough energy to light a 100-watt bulb for nearly 20 days.

Grain, meat and even energy are roped together in a way that could have dire results. More meat means a corresponding increase in demand for feed, especially corn and soy, which some experts say will contribute to higher prices.

This will be inconvenient for citizens of wealthier nations, but it could have tragic consequences for those of poorer ones, especially if higher prices for feed divert production away from food crops. The demand for ethanol is already pushing up prices, and explains, in part, the 40 percent rise last year in the food price index calculated by the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organization.

Though some 800 million people on the planet now suffer from hunger or malnutrition, the majority of corn and soy grown in the world feeds cattle, pigs and chickens. This despite the inherent inefficiencies: about two to five times more grain is required to produce the same amount of calories through livestock as through direct grain consumption, according to Rosamond Naylor, an associate professor of economics at Stanford University. It is as much as 10 times more in the case of grain-fed beef in the United States.

The environmental impact of growing so much grain for animal feed is profound. Agriculture in the United States — much of which now serves the demand for meat — contributes to nearly three-quarters of all water-quality problems in the nation’s rivers and streams, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Because the stomachs of cattle are meant to digest grass, not grain, cattle raised industrially thrive only in the sense that they gain weight quickly. This diet made it possible to remove cattle from their natural environment and encourage the efficiency of mass confinement and slaughter. But it causes enough health problems that administration of antibiotics is routine, so much so that it can result in antibiotic-resistant bacteria that threaten the usefulness of medicines that treat people.

Those grain-fed animals, in turn, are contributing to health problems among the world’s wealthier citizens — heart disease, some types of cancer, diabetes. The argument that meat provides useful protein makes sense, if the quantities are small. But the “you gotta eat meat” claim collapses at American levels. Even if the amount of meat we eat weren’t harmful, it’s way more than enough.

Americans are downing close to 200 pounds of meat, poultry and fish per capita per year (dairy and eggs are separate, and hardly insignificant), an increase of 50 pounds per person from 50 years ago. We each consume something like 110 grams of protein a day, about twice the federal government’s recommended allowance; of that, about 75 grams come from animal protein. (The recommended level is itself considered by many dietary experts to be higher than it needs to be.) It’s likely that most of us would do just fine on around 30 grams of protein a day, virtually all of it from plant sources .

What can be done? There’s no simple answer. Better waste management, for one. Eliminating subsidies would also help; the United Nations estimates that they account for 31 percent of global farm income. Improved farming practices would help, too. Mark W. Rosegrant, director of environment and production technology at the nonprofit International Food Policy Research Institute, says, “There should be investment in livestock breeding and management, to reduce the footprint needed to produce any given level of meat.”

Then there’s technology. Israel and Korea are among the countries experimenting with using animal waste to generate electricity. Some of the biggest hog operations in the United States are working, with some success, to turn manure into fuel.

Longer term, it no longer seems lunacy to believe in the possibility of “meat without feet” — meat produced in vitro, by growing animal cells in a super-rich nutrient environment before being further manipulated into burgers and steaks.

Another suggestion is a return to grazing beef, a very real alternative as long as you accept the psychologically difficult and politically unpopular notion of eating less of it. That’s because grazing could never produce as many cattle as feedlots do. Still, said Michael Pollan, author of the recent book “In Defense of Food,” “In places where you can’t grow grain, fattening cows on grass is always going to make more sense.”

But pigs and chickens, which convert grain to meat far more efficiently than beef, are increasingly the meats of choice for producers, accounting for 70 percent of total meat production, with industrialized systems producing half that pork and three-quarters of the chicken.

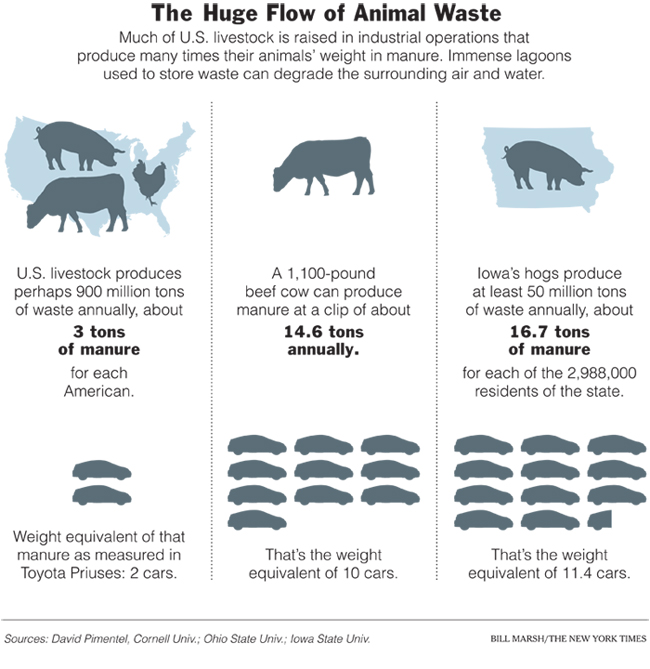

Once, these animals were raised locally (even many New Yorkers remember the pigs of Secaucus), reducing transportation costs and allowing their manure to be spread on nearby fields. Now hog production facilities that resemble prisons more than farms are hundreds of miles from major population centers, and their manure “lagoons” pollute streams and groundwater. (In Iowa alone, hog factories and farms produce more than 50 million tons of excrement annually.)

These problems originated here, but are no longer limited to the United States. While the domestic demand for meat has leveled off, the industrial production of livestock is growing more than twice as fast as land-based methods, according to the United Nations.

Perhaps the best hope for change lies in consumers’ becoming aware of the true costs of industrial meat production. “When you look at environmental problems in the U.S.,” says Professor Eshel, “nearly all of them have their source in food production and in particular meat production. And factory farming is ‘optimal’ only as long as degrading waterways is free. If dumping this stuff becomes costly — even if it simply carries a non-zero price tag — the entire structure of food production will change dramatically.”

Animal welfare may not yet be a major concern, but as the horrors of raising meat in confinement become known, more animal lovers may start to react. And would the world not be a better place were some of the grain we use to grow meat directed instead to feed our fellow human beings?

Real prices of beef, pork and poultry have held steady, perhaps even decreased, for 40 years or more (in part because of grain subsidies), though we’re beginning to see them increase now. But many experts, including Tyler Cowen, a professor of economics at George Mason University, say they don’t believe meat prices will rise high enough to affect demand in the United States.

“I just don’t think we can count on market prices to reduce our meat consumption,” he said. “There may be a temporary spike in food prices, but it will almost certainly be reversed and then some. But if all the burden is put on eaters, that’s not a tragic state of affairs.”

If price spikes don’t change eating habits, perhaps the combination of deforestation, pollution, climate change, starvation, heart disease and animal cruelty will gradually encourage the simple daily act of eating more plants and fewer animals.

Mr. Rosegrant of the food policy research institute says he foresees “a stronger public relations campaign in the reduction of meat consumption — one like that around cigarettes — emphasizing personal health, compassion for animals, and doing good for the poor and the planet.”

It wouldn’t surprise Professor Eshel if all of this had a real impact. “The good of people’s bodies and the good of the planet are more or less perfectly aligned,” he said.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, in its detailed 2006 study of the impact of meat consumption on the planet, “Livestock’s Long Shadow,” made a similar point: “There are reasons for optimism that the conflicting demands for animal products and environmental services can be reconciled. Both demands are exerted by the same group of people ... the relatively affluent, middle- to high-income class, which is no longer confined to industrialized countries. ... This group of consumers is probably ready to use its growing voice to exert pressure for change and may be willing to absorb the inevitable price increases.”

In fact, Americans are already buying more environmentally friendly products, choosing more sustainably produced meat, eggs and dairy. The number of farmers’ markets has more than doubled in the last 10 years or so, and it has escaped no one’s notice that the organic food market is growing fast. These all represent products that are more expensive but of higher quality.

If those trends continue, meat may become a treat rather than a routine. It won’t be uncommon, but just as surely as the S.U.V. will yield to the hybrid, the half-pound-a-day meat era will end.

Maybe that’s not such a big deal. “Who said people had to eat meat three times a day?” asked Mr. Pollan.